Mad Men Unbuttoned (blog) is Natasha Vargas-Cooper’s expansion of her morning-after columns for the Awl, which were just concise enough to work in that medium.

The first warning sign is Vargas-Cooper’s agent, Kate Lee, who rocketed to blogger-like microfame after the New Yorker treated the subject of blogs-to-books six excruciating years ago. In my direct experience, the snippy, dismissive Lee early on manifested what became the inescapable rule: “Bloggers” with no experience writing for print got the book deals, while any writer who merely ran a blog was deemed overqualified. As with the cyberbullying medium known as Tumblr, “[i]t’s gotten to the point where the stupider you are, the farther away from real writers you situate yourself on the career axis, the likelier you are to score a book contract.”

The authoress is in no way stupid and surely knows a lot of print journos. With the project’s high-end-pop-culture hook unsullied by cheezburger juvenilia, surely “expanding” the Awl postings into a book was a no-brainer. But as we’ve found with so many other blogs-to-books, new wine tastes sour in old bottles.

Who is this book for?

I can’t believe for a moment that readers will never have watched Mad Men. As a compendium of trivia – that’s what it is; it’s like a Nitpicker’s Guide to Mad Men – the readership is clearly dominated by fans of the show. As such, why in the world are we given a smug little cast-of-characters list at the front of the book?

That list reminds me of a technique used since the days of Star Trek to build up a fanbase: Offering just enough “biographical” trivia about a character to a teenage boy can one-up his friends and indulge his echt-male monomania. (“Bender [full name: Bender Bending Rodríguez], also known as Bending Unit 22, was made in Tijuana, Mexico in 2997.”) Three in a row from Mad Men Unbuttoned:

- Sally Draper

- Prepubescent daughter of Betty and Don. Daddy’s girl.

- Carol McCardy

- Joan’s former roommate and closet lesbian.

- Suzanne Farrell

- Don’s most recent extramarital affair [since what date?]. Sally Draper’s bright-eyed schoolteacher [as opposed to a teacher of some other Sally?]. Alludes to having bedded more than one suburban father. Bakes date nut bread [sic].

After a while, this sort of thing becomes a parody of itself. If you really walked into the topic of Mad Men cold and had never watched an episode, would you be reading this book? Would these descriptions actually tell you anything of use?

Does this book understand it isn’t a blog?

I don’t think it does. The book has not chapters but “entries,” some of them by guest writers whose bios are endlessly footnoted instead of just presented in a dek or compiled in an endpaper Contributors section. Writing a book is a lengthy project that has no kinship whatsoever with churning out twelve “entries” a day. What we have here is a failure to scale.

With few exceptions, entries are short, typically a page and a half. I don’t know why Vargas-Cooper didn’t have the courage of her convictions to write single-graf entries if necessary. I guess that seems too abbreviated and bloglike. (I thought they were “entries.”) But even at a page and a half, chapters come off as padded, gassy, comma-addled, and lethargic, almost as if stalling for time in an undergraduate essay. (In a real essay, it would make use of dodges like wider margins and a bigger size of Arial as “typeface.”)

And actually, the endless footnotes and lengthy quotations smack of undergraduates’ relief at having Googled a source they could just plunk right into the text. The examples are just nonobvious enough to assure a teaching assistant that no, I did not actually cite Wikipedia in my essay. Footnotes and quotations festooning such short “entries” signify lack of depth even while the original blog posts were just detailed enough. On the Awl, researching a relevant citation and calling it a footnote worked great; in the book, dropping in an obvious quotation from a Googlable source and footnoting it for real is a total dud.

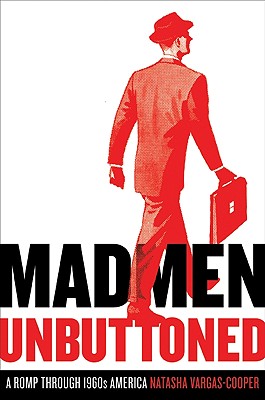

A garish book about a design-conscious show

An experienced designer, Renato Stanišić, is credited in the front matter. (I couldn’t find a way to contact him. I suppose if I were better connected, that wouldn’t be a problem.) I understand the rather generic mid-century-design reference communicated by the book’s colour palette, a Roger Black–compliant black, white, and red. But when considered together with the book’s typography and coated stock, the effect is garish and loud.

An experienced designer, Renato Stanišić, is credited in the front matter. (I couldn’t find a way to contact him. I suppose if I were better connected, that wouldn’t be a problem.) I understand the rather generic mid-century-design reference communicated by the book’s colour palette, a Roger Black–compliant black, white, and red. But when considered together with the book’s typography and coated stock, the effect is garish and loud.

-

Heds are – inevitably – set in Helvetica, but Condensed and with poor letterspacing. (Chapter-break pages use full-width Helvetica and another grotesk for numerals; the cover is in Knockout. [Photos.])

-

Just as we’re waiting for aging newspapermen to die out and be replaced by some form of digital native, we are waiting for book designers with their noses in the air to suffer a similar fate, metaphorically speaking. At some point, 21st-century book designers are going to have to learn that hot-metal typefaces from a previous century do not work for present-day topics or printing conditions.

Stempel Garamond, used here, is a case in point. Letterpress typefaces relied on ink spread to add an air of softness. (That’s what Ličko found lacking in photosetting and computer versions of Baskerville and set out to restore with Mrs Eaves.) It is a settled matter that 20th-century metal typefaces look spindly and overprecise in outline type. Printing such faces on tack-sharp coated stock makes matters worse, turning even a face with diagonal stress (cf. Middendorp) into a de facto Transitional with too much dazzle and contrast.

We now have at our disposal a reproduction method that works well as a simulation of offset-printed coated stock: Colour laser printing on colour-laser paper. Any typeface that stands up well under the latter conditions will do so under the former. I assure you that any 21st-century book face will have been tested by laser-printing it onto coated stock, and if it works there, it’ll work when printed offset. Those are the fonts we should be using for 21st-century books, not relics from a previous century that are in fact shadows of their former selves.

Why bother trying to show how classy and educated you are – “I use Garamond like a true aficionado” – when the exact printing mechanism you use vitiates the true nature of the typeface? Why not show real acumen and use a font that can actually handle the conditions you’re using to print it? (And actually, any form of offset printing, even on uncoated book stock, will undermine hot-metal typefaces.)

In an expected bout of half-assery, what is clearly in use here is some old Type 1 copy of the font instead of a full TrueType version with all ligatures in place. (Words like office and official end up looking like of fice and of ficial.) I assume Stanišić already had that Type 1 copy on his machine and nobody wanted to pony up for a newer version at a measly $119.

I guess it’s easier just to hide behind the lie, which I heard from a book designer at Word on the Street 2009, that we really only have five or ten typefaces we can use for books. Tschichold might have had that few, sure, but he is long since dead.

I have a host of other complaints about the design, including inconsistent-yet-still-garish handling of bulleted lists (a whole new kind appears on p. 92) and an atrocious set of illustration credits (pp. 225–226) that looks like a dump from Microsoft Word.

At least copy-editing is much better than one would expect. Of course there are still errors.

-

VWs did not have “lack of flare” (p. 27).

-

“Every one” isn’t two words (p. 9 note 1).

-

MCCARDY is not written thus in all-caps (there’s only one cap C).

-

I guess writing out numbers is just so much classier and more booklike than following established style. Still: “500,000” Beetles but “two million” copies of Lady Chatterley’s Lover?

-

I didn’t mind the photos, even if some were so generic as to be placeholders. Nicola Tamindzić’s authoress photo should not have appeared on inside back page and also inside back flap. If you’re going to talk about Enovid, an early birth-control pill, don’t show us a picture of half a dozen pills that aren’t Enovid.

Organization is a mess

The book is divided into nine sections, meaning the same topics, even the same phrase, appear over and over again in different sections. This is not a reference book that readers will dip into in the hopes of finding an answer to a single question, then put back on the shelf till the next question comes up. Again, the book does not understand its own readership, which is one of completists who will read the thing from cover to cover. These are not blog posts uploaded on different days a reader can assemble into sequence by clicking a category or tag.

-

Is J. Press a men’s clothing store? It says so on p. 63 – then again on 66.

-

The two Menken pieces (24, 73) need to go together. So do the pieces on lesbians (105). So do the references on photography supplanting illustration (41, 109); Don’s bon mot to Sal (“Limit your exposure,” xvii, 111); and the treatments of divorce and Reno (88, 112, 221, 231; the index muffs the latter) and of contraception (95, 115). The topic of smoking is allocated ten pages spread out all over the place.

-

We read about pregnancy classes (118), then there’s a full section break immediately followed by another “entry” on pregnancy. Japonisme and shoguns aren’t two topics, yet there they are right after each other. (We don’t need to be quite so patronized as to have japonisme and chinoiserie defined for us.)

The entire treatment of the Draper house’s interior design (137, 139, 149) should really be a full chapter. (So much woolgathering on japonisme, yet nary a mention of fainting couches?)

-

The stewardess “entry” seems superfluous at best.

-

Every reader, every single one, will already know what Metropolis is, an almost insulting lecture (186).

Vargas-Cooper is particularly weak at starting new topics. (“Servants! What an emotionally fraught and ambiguous place they hold in American life” [87]; “Let’s spend some time in Bert Cooper’s office”s [142].) Wrapping topics up is an occasional problem; the issue of Joan and interior design (141) is atrociously handled.

Indeed, Vargas-Cooper blows a golden opportunity in the close of her “entry” on psychotherapy (p. 133). Its autobiographical details – from what I can tell unique in the whole book – come off like passive-aggressive asides that no shrink, or the showrunner on In Treatment, would let you get away with. I thought that’s why we have editors. I keep thinking that for some reason.

Even accepting Stuff White People Like as an outlier (with lousy type and paper of its own sort), it seems unequivocal that blogs-to-books simply do not work. Vargas-Cooper, who wouldn’t comment for this “entry,” deserves the money she made, but the topic deserved to stay on a blog.