Camille Paglia (yes), Glittering Images:

-

On Mondrian:

At first, Mondrian used blended colours against a grey background; then he shifted to bold primary colours against white. For the rest of his career, his only colours were red, blue, and yellow. He scrapped chiaroscuro, the shading by which Renaissance and Baroque painters created volume…. He built up his white areas so that they did not recede, falsely implying depth. Everything for him had to operate on and across the surface.

What reproductions cannot catch is the texture of Mondrian’s brushstrokes, grooving his whites in contrasting directions. Mondrian’s black lines became more prominent in the 1920s, with horizontals usually thicker than verticals. He said his black lines were “deadly” until he glossed them with shiny varnish.

Structure always came first: He sketched lines in charcoal on paper or canvas and added colour later. Mondrian’s lines hypothetically shoot out into infinite space, creating a charged new relationship between a painting and its surroundings. Hence his revolutionary step of discarding the frame, that heavy, ornate golden rim of traditional portable paintings. Thanks to Mondrian’s innovation, every department store today sells narrow black frames and frameless plastic blocks for mounting art and photographs.

-

On Pollock:

His whirling lines hover in a strange, unidentifiable zone between his very shallow background and the rough surface, thickly layered with pigment and sometimes embedded with actual objects…. Pollock’s textured pictures have the shadowed concreteness of sculpture – the genre toward which he had first aspired.

Pollock’s colossal paintings are impossible to appreciate in reproductions, which shrink them to a dismal page. Seen in person, they overwhelm the visitor with their majesty. Only close-up snapshots of details can convey the mesmerizing intricacy of those rippling, tangled surfaces, sprinkled with sand and glinting with metallic paint and broken glass.

Now one considers a densely entitled but extremely valuable book: Reductionism in Art and Brain Science: Bridging the Two Cultures by Nobelist Eric Kandel. In this well typeset, easily understood triumph of explaining science to laypeople, Kandel carefully paces an explanation of how the brain processes visual stimuli and matches those revelations to the progression of the way painters have dealt with faces (particularly), to some extent landscape, and figure/ground relations.

Two facts Kandel teaches us:

-

The classic beholder’s share describes the contribution that the human visual processing system makes to understanding the world. An object does not exist by itself but is also interpreted by the eye, retina, and brain. You the viewer complete the picture, which does not exist without you (by definition). This indeed has the disturbing philosophical implication that the world does not exist unless we look at it. (I wonder what that means for blind people.)

-

You see the object first, then, later in time, you discern its texture.

-

The texture of an object activates cells in a neighbouring region of the brain, the medial occipital cortex, regardless of whether the object is perceived by the eye or by the hand…. This relationship is thought to explain, in part, why we can easily identify and distinguish between the different materials of an object – skin, cloth, wood, or metal – and can often do so at a glance.

Surprisingly even to me, I can tell you what category of plastic an object is made of at a glance (polyethylene, polypropylene, ABS, PET, polycarbonate [not a “plastic”]).

I assume this also has something to do with the ability – not always accurate – of experts in art forgery and theft to identify a forgery on sight. Or the countless other visual processes that happen instantly and can’t be made to happen if you invest more time into them.

-

When we first look at a painting or any other object, our brain processes only visual information. Shortly thereafter, additional information processed by other senses is thought to come into play, resulting in a multisensory representation of the object in higher regions of the brain….

In fact, the perception of texture, which is central to both Willem de Kooning’s and Jackson Pollock’s paintings, is intimately tied to visual discrimination and to associations in these higher regions of the brain…, which have robust and efficient mechanisms for processing textured images. Combining information from several senses is critical to the brain’s perception of art.

-

Pace the unsympathetic Gerry Leonidas (but the older one gets in typography, the less sympathetic one becomes), you must always inspect the original object. Actually, I see that is the University of Reading’s observation (but Leonidas is in a picture there):

Our collections span early printing, the development of newspapers, ephemera, corporate identity, British modernism, and many other areas. We are particularly strong in type-related areas, with extensive collections of historical and contemporary type specimens, original drawings for many scripts, wood and metal letters, and letterpress as well as hot-metal equipment.

We make near-constant use of our collections…. For example, when discussing Greek we examine original editions covering the full 5½ centuries of Greek printing….

We always work with original artifacts: Experiencing the scale, material, and reproduction technology of designed matter is essential for understanding why this is worth discussing.

-

The experience of letterpress type fits Kandel’s description exactly: You read the letters and you perceive their dimensionality.

-

I also suspect that these perceptual stages explain why even type-naïve persons can evaluate how well a layout works by looking at it upside-down. I also find I have a different sensation, for want of a better word, when looking at layouts in scripts I can’t read, even though I still spot errors in such layouts (like rivers).

-

There are reasons to look at things, and the pleasure and edification we get from looking at them, which lasts only the time we spend so doing, is worth it. Not everything has to be written down or set in stone, and not every experience has to stand the test of time.

As I tend to do these days, I sat on the vegan meat substitute of this posting for quite a while. I imagined myself trying to explain the delight and excitement of the well-known facts about visual perception that I never even knew about. I associated it with a literal lifetime’s pleasure at beholding printed objects – and indeed quite a few artworks, colour-field works especially.

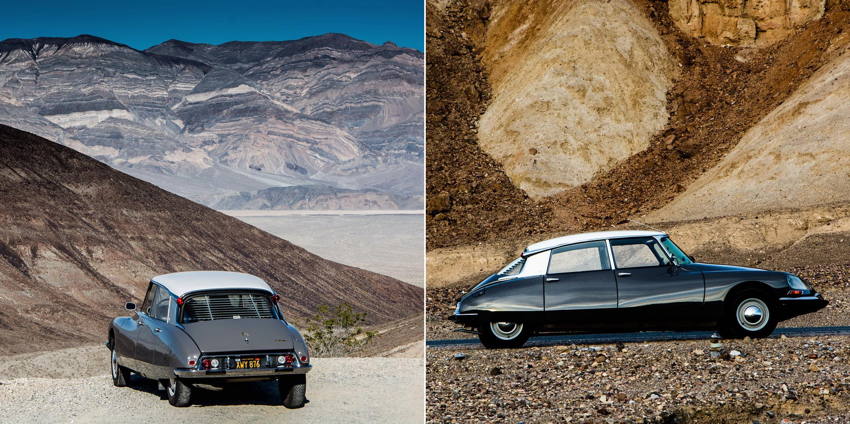

I certainly better understand why I like cars without being able to drive, and why, for example, apperception of a perfect Citroën DS – situated in Death Valley, in the present day – borders on a religious experience.

And these are just pictures, for God’s sake. (Digging these up right now [via Jeff Suhy], I actually muttered “Mother of God.”)

But as sure as texture follows image, I then got discouraged right away, because I’ve been trying to impart my knowledge for 20 years and how’s that been going for me.