I have read Generation X and all the English-language nonfiction books by Douglas Coupland, declared by some groups to be the voice of another group’s generation. (There’s a Japan-only book almost nobody over here has read, including me.) I read Microserfs, and the considerably superior short story of the same title in Wired. I enjoyed City of Glass, a return to glib throwaway folk etymology (Vancouver condos are see-throughs), and I like both volumes of Souvenir of Canada.

You will have heard of the documentary based on those books, directed by Robin Neinstein. It is flatly awful, and it has pushed me well past my limit of tolerance of this doughy drumstick masquerading as an intellectual.

-

First, let’s attack Neinstein (also art director Rhonda Moscoe) for epitomizing glib throwaway culture, the actual premise of the film, in the film itself. Of course I’m talking about typography. There’s a failed effort to duplicate the appearance of the Canada Wordmark – a too-plain stacking of bilingual Helvetica lines – in the film’s actual credits.

It’s not as though they didn’t have the real thing at their disposal. Here’s Coupland in what he continually reminds us is one of his favourite spots, Vancouver airport.

There’s the real thing right in front of him. Now, what’s the film’s hand-drawn facsimile? Arial, of course.

(Yeah, that’s great writing there. Also, hint: You use italics for book titles, not quotation marks, and certainly not neutral quotes. Congrats on finding a way to make a bad font worse.)

It goes on and on:

Note the failed simulacrum of the Canada wordmark. (Still can’t tell the diff, apparently.)

And Arial is, inevitably, used as a titling font throughout the picture. It goes without saying that a little ting! is heard as we freeze-frame on each of these titles. How kooky. How Dag and Elvissa.

(Neutral apostrophe, note.)

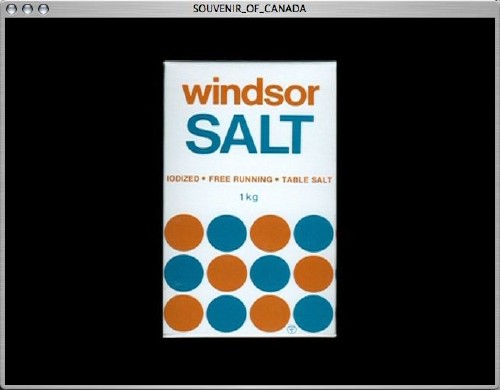

Here’s a secret that Coupland and Neinstein aren’t telling you. The Windsor salt box, and nearly everything in the two books, is an undesigned product.

Calling it well-designed after the fact is disingenuous nostalgia. Arial is an undesigned font. Using it in this context doesn’t even reach the level of disingenuousness. It’s just undesign. (And don’t think for a second that, in 25 years, Arial will be looked back upon affectionately as a kitschy lodestar of the Aughties.)

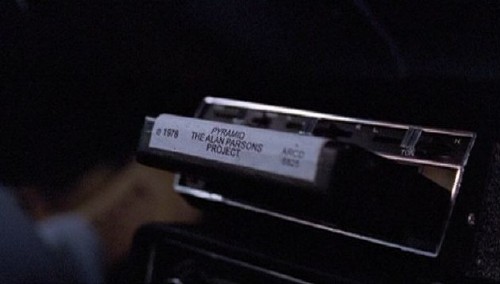

I rather doubt this is exactly what the spine of an Alan Parsons Project 8-track looked like in its heyday, if only because Arial hadn’t been designed yet. Doesn’t that look like a taped-on label to you?

-

The movie is all about looking back, and comes complete with charming re-enactments of Coupland’s young life, portrayed by an actor with more and different hair (curly, for starters) who is at least several grades higher up the food chain than Coupland is. That isn’t saying much.

Coupland has really put himself out in public more in recent years, including starring in a film adaptation of his nonfiction books. That forces us to look at him a lot more than before. I saw Coupland in a reading on Queen St. over a decade ago and was surprised at how short, plain, and soft-spoken he was (he cannot project). The intervening years have made it clear that he isn’t just plain, he’s homely – on a good day. And he can’t dress. In fact, here he is introducing the film:

He’s got bad hair and complexion and is just as out-of-shape as I am, though I probably have better legs from engaging in the echt-Vancouver activity of all-year bicycling.

We get a lot of close-ups of the face, by the way, often through the original cinematic trope of watching Coupland gaze out an airplane window.

As if he’d ever fly coach. (Like, he flew coach to Italy to “interview” Morrissey?) He was only back there in steerage because that’s all the filmmakers could afford.

And the voice! Jesus, his gravelly Doppler-effect whine is so devoid of intonation he sounds like a diesel Rabbit dragging its muffler down the street.

And remember: This guy is a visual artist, novelist, and essayist, and an homosexualist, yet has no style. The voice of which generation?

-

The gay business might explain why he called his mother one day and told her not to touch her kitchen because he was coming over to photograph it. And why his gestures are those of a mid-’70s mom.

The movie rolls footage of an anthropological experiment in which an overintellectualizing Coupland watches hockey fights with his brother, who uses body language to put as much distance as he possibly can between them.

Yeah. Doug Coupland and hockey. Yeah. At a time like this, what else does one do but cite An Arrow’s Flight?

It was into this parody of domestic life that Pyrrus was born; in it he lived his formative years. If there are such years, if we aren’t pretty much formed by the time we see light. For example: If Pyrrhus wasn’t born a sissy, he certainly was one by the time his father first playfully wrestled with him, when he was two or three. He cried when real boys were supposed to laugh; he ran away from frogs and even butterflies; if you threw a ball at him he covered his face with his hands instead of trying to catch it. There are fathers who try to remedy this: “At-ten-hut! We will play catch now!” All they get is sons like Leucon, who nurse permanent grievances and still can’t catch.

-

Symbolically, even while wearing extremely supermacho protective booties, it takes three attempts for Coupland to break a hockey stick by jumping on it.

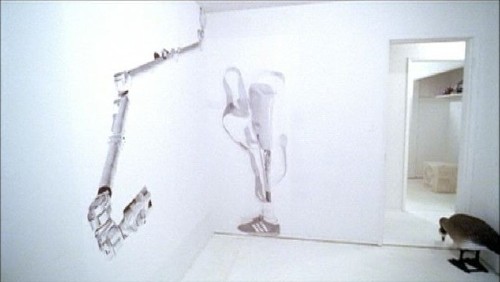

Note the found-object “sculpture” of some kind of molecule made out of water-cooler bottles. Much is made of Coupland’s twee art installations entitled Canada House – first at a condemned tract house in Vancouver, then another one even more artificially situated, at the coïncidentally-named Canada House in London. (Apparently it also ran in some form at the Design Exchange, another indicator of the DX’s curatorial acumen.) The whole tract house was painted white (the booties keep everything pristine – viewers of art as despoilers of art). The exhibit came complete with matching white-on-white displays.

Sometimes that worked, as with his pairing of the Canadarm and Terry Fox’s leg.

Coupland is simply obsessed with saintly, doomed Terry Fox, whom Coupland’s actor stand-in resembles. Here’s the Terry Fox sock:

But he’s not at all interested in white-trash, doomed Steve Fonyo or half-muscular, half-skeletal, still-goin’-strong Rick Hansen.

Ostensibly the goods displayed in the House were meant to evoke a Canada of the ’70s, but I didn’t recognize half of them, very much including the furniture.

-

Coupland tried to arrange for a raccoon to run amok in a “superabundant environment” of a miniature city made of food. (In a title, curiously typeset in Helvetica, the film called the creature a “racoon.”) But, like a peevish director firing a starlet for refusing to blow him, after meeting the raccoon the artist scotched the plans: “It’s like someone who’s had the worst day ever flying around on a plane – like, just ready to snap at any moment. You know, it’d be different if it was another animal, but I just couldn’t do it with a raccoon.”

-

It was pleasing to witness the destruction of Canada House.

I would have been more pleased if the artifacts had still been in there.

-

Eventually Coupland gets around to complaining about his critical reception. I knew that was gonna happen. “My first novel surprised me with its success,” he states as we are shown a close-up of Generation X. I suppose that’s consistent with how many publishers rejected it first. Critics kept dismissing him as overly American in tone, content, or influence. It’s a fair cop, of course. Unlike Tyler Brûlé, he’s the wrong kind of transnational Trudeau-era Canadian. You’re supposed to be really transnational; you aren’t supposed to just move to Palm Springs and set your novels in the States. “Because now I’m doing books on Canada, and ‘Nope, still not Canadian,’ ” he complains, using a curious turn of phrase (“doing books”) that makes sense in some ways: They’re just little art objects to him, literally feedstock. Best-selling art objects that produce millions in revenue, but objects nonetheless. Certainly not something to be read.

It’s been a source of frustration over the years that I cannot find a chapter in a book I read in which the writer was driven to Coupland’s house in his Audi and given a tour of his art collection, which the writer was to keep secret at any cost. Subsequently I read descriptions of that collection, which I also cannot find [Times slideshow]. Everything’s a product to him – formerly a secret product (like being in the closet), now much more out in the open. And the big advantage he has, he tells us in the film, is the short time elapsed between coming up with an idea and “implementation.” Other people “overthink” it, he says, overlooking the fact that he’s rich enough to fund his own projects at whim. They can be thrown together with next to no thought whatsoever, and it doesn’t matter what the critics think, because there’s always another product on the horizon, another product that people eagerly await. He’s got fans who are like half of Courtney Love’s – the half that laughs off her latest mischief with a breezy “Oh, that’s our Courtney!”

Some people are taken in by this hooey, among them Robin Neinstein and public-sector funding bodies that paid for the movie. And now we’re letting Coupland write his own scripts.