(UPDATED) This year we endured two reports claiming to address the urgent horrible discrimination women in film and television face. I fact-checked their asses.

-

One, from Ryerson professor Michael Coutanche and coauthors, does a good job of covering a lot of issues and provides a great deal of data. Only one section leapt out at me, and it was this anonymized quote from a wymmyn screenwriter:

The kinds of stories women are interested in writing are often not the kinds of stories [that broadcasters want], and the characters that populate them are not considered commercial. Even with all the crap floating around about female-driven stories, male screenwriters still get hired to write them more frequently then female screenwriters. Film and television are male-dominated industries even if there are more women producers and executives [than before]. Those women tend to hire men more often than women and they tend to choose projects that go along with the male-dominated ideas of what is commercial.

As a writer, I find this ridiculous on its face. I asked Coutanche these questions, which he dodged in his reply:

What are “[t]he kinds of stories women are interested in writing”? (Does that include lesbians, by the way?) What are her examples of those “kinds of stories”?

If a male writer cannot write plausible female characters, doesn’t that writer, plainly, suck? (And conversely with female writers and male characters?) Next this source is gonna tell us only blacks can write stories about blacks. (Actually, I note that directly comparable arguments were not made by your “racialized minority” respondents.)

Why didn’t you ask any of these questions, instead of just copying and pasting warmed-over liberal-feminist arguments about how women are an irreducible entity subject to endless systemic and – apparently – systematic discrimination?

Let’s keep going with that line of questioning.

-

I don’t know what “[t]he kinds of stories women are interested in writing” are. Does that include lesbians? What are the kinds of stories lesbians want to write?

-

What are the kinds of stories Peggy Atwood wants to write? Ursula LeGuin? Lauren Beukes?

-

If there really are women’s stories, why did Douglas Sirk direct so many of them?

-

Why was Battlestar Galactica praised for its near-complete gender neutrality? Its “strong” female characters – a type that is “tough, cold, terse, taciturn and prone to not saying goodbye when they hang up the phone” – were written by men.

And Caprica, which seemingly only I liked, went much further: It was a science-fiction series that revolved entirely around three teenage girls, one reanimated in a killer robot’s body.

-

And, I dunno, doesn’t Bruce Davis’s lover in Longtime Companion bitch that if he can’t write a plausible woman or black character, he stinks as a writer?

Really, why in the name of God are we lending credence to this lie? How does the story know you’re a girl and what is stopping you from writing it?

-

-

The other report, by a pressure group called Women in View, is almost but not quite an abomination. And like all “studies” that make the lot of women and nonwhites sound dire, it got tons of coverage in the liberal media. (I apologize for sounding like a right-wing asshole in the previous sentence. It was the only terminology that accurately fit the facts.)

I asked Women in View the following (along the way criticizing their typesetting – also a problem with the Ryerson report).

-

Why did you choose the stigmatized, ultra-left-wing term “racialized minorities” instead of the value-neutral Canadian English “visible minorities”?

-

Though you offer no statistics to back up your claim that women occupy “close to half the labour pool,” on what do you base the fundamental assumption of your report, your organization, and, I gather, your career – that women deserve a proportion of all jobs equal to their proportion of the population in general? Stated another way, Women in View does not actually seek an “equitable” outcome; it identifies male-dominated jobs in the film and television industries as desirable and expects women to get half of them. Isn’t that accurate?

-

What statistics did you use to back up the claim that women in “top-most echelons,” and in fact women “at almost every level,” “earn less than their male counterparts”? Did the statistics you used – surely you used statistics – control for education, work experience, and gaps in labour-force participation?

-

Why did you not state the fact that at least three of the series you surveyed – Being Erica; Flashpoint; and Little Mosque on the Prairie – were created by women? Why did you not disclose that these women were a large percentage of the writers who wrote more than one episode each? (The proportions of males and females writing two or more episodes each is almost the same, you failed to note: 16 ÷ 48 = 0.25; 38 ÷ 133 = 0.29.)

-

Why is the report focussed solely on women and nonwhites when other groups arguably deserve equal scrutiny? Your focus on those two favoured liberal targets led you to ignore the fact that – just to give one example – the showrunner, lead writer, and, in all practical senses, the co-creator of Being Erica is gay. I thought gays were almost as good as women in your circle? Don’t we count? (You were happy in the report to discuss First Nations writers erratically and at random points. So obviously you weren’t concerned solely with women and visible minorities. I expect people with disabilities would have a similar bone to pick with you. And actually, so do I on that point.)

-

While the alarmist tone of the numbers you publish may or may not be justified, I fail to see how female screenwriters’ accounting for 36% of positions indicates that they are at anything resembling a real disadvantage. I’m sure you would agree, at least if you compare screenwriters’ lot to cinematographers’.

-

How is it in any way worse for a woman who is also a “racialized minority” or a native to be denied a job compared to a white woman (pp. 6–7)? (The report is premised on prevalent illegal discrimination. You assume that women, vizmins, and natives are simply denied jobs.)

-

Where is the evidence that there actually are enough qualified applicants in Canada for all the covered positions to actually work half of all jobs were they even offered?

I doubt you’ve ever had to face questions like these in your life. Nor do I have any illusions as to how you’ll respond. I will duly report any such response – or nonresponse.

(Women in View indeed nonresponded.)

And here’s another question for you: If you really believe (p. 8; emphasis added) that “Canadian women have the right to expect fair access to employment and professional fulfillment,” why is your entire report premised on equality of outcome (50% of all jobs everywhere, with visible minorities and natives also getting 50% each)?

-

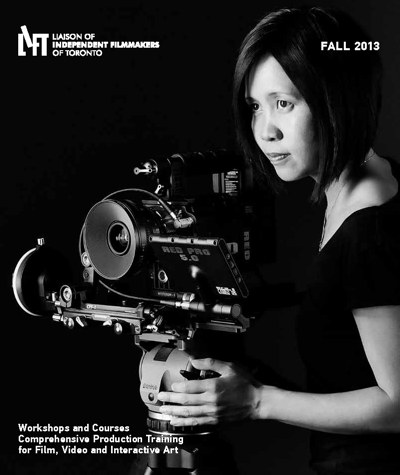

Fact-checking the status of women cinematographers

I was particularly annoyed at the Women in View report’s complaint that female Canadian cinematographeuses were not employed at all in the limited survey of this report. So I checked the Canadian Society of Cinematographers’ Web site. They wouldn’t answer my E-mail, but I simply went through their entire member directory and found 436 male names, 21 female, and 25 ambiguous. At least some of those males would be disqualified because they’re based in Australia or other countries, I noted in passing. But, in gross numbers, there are 20 times as many qualified male cinematographers in Canada as female ones.

We have a lot of episodic TV episodes shot here, plus many foreign-funded movies and a few Canadian movies. If all 20 or so cinematographeuses were well qualified, they could presumably work all the time with lots of room left over for male cinematographers. But that is not remotely the point made by the report, which in fact makes no point other than to decry womyn cinematographers’ compete absence from the sample. That could be explained any number of ways, including years of experience, taking time off to raise kids, and numerical rarity. (Or by the fact that the year studied was an outlier.)

But there was no effort to explain it. It’s simply a claim that we’re expected to be terribly, horribly shocked by.

I didn’t stop there. I looked through the list again and located every cinematographeuse with an E-mail address and contacted them. A few responded.

Zoe Dirse

I had a nice telephone interview with Zoe Dirse. Only six women are full CSC members, she says. She’s one of the six. (I couldn’t verify that because CSC doesn’t answer my mail. I suppose I could try extra-hard, but I haven’t so far.)

-

Why should women become cinematographers? (This is my central question, actually.) “Maybe the fact that it’s a lot of fun to be in that world. You know, when you’re in that club it can become very male-defined. I’ve been in those situations where I’ve been the only woman on a film crew and there is a bit of a boys’ club happening, but then again, that isn’t something that deters me.”

Now she’s an instructor at Sheridan College. “Role modelling’s a big thing…. I actually looked, back before Internet and all that, just by watching films: Where are the female cinematographers out there in the world?” She found only one but thought “ ‘OK, that’s enough for me! She did it – I can do it!’ But I feel that’s a big impediment….

“By the time they get to final year, they’re pretty much discouraged…. If I’m sort of a constant presence for them through the entire several years, then there’ll be more [women]…. When I get pulled out of that kind of equation, then there’s less.” She blossomed because she got hired by the NFB in its heyday. Full-time job with terrific mentors, both men and women. “Cinematography is a craft…. The best cinematographers in the world were mentored by some of the best people around them.”

-

We had quite a conversation about taking or making the leap from camera assistant to camera operator or cinematographer or director of photography. Dirse broadly agreed that fewer women even try to make that leap. I don’t agree with the role-model hypothesis, but Dirse does, and told me that Iris Ng, DP on Stories We Tell, made the push from assistant to operator after having read an article about Dirse. (Iris confirmed that, actually: “I was working at a camera-rental house when I read the article about Zoe, which gave me a push.” But she didn’t really want to talk too much more about the issues.)

We had quite a conversation about taking or making the leap from camera assistant to camera operator or cinematographer or director of photography. Dirse broadly agreed that fewer women even try to make that leap. I don’t agree with the role-model hypothesis, but Dirse does, and told me that Iris Ng, DP on Stories We Tell, made the push from assistant to operator after having read an article about Dirse. (Iris confirmed that, actually: “I was working at a camera-rental house when I read the article about Zoe, which gave me a push.” But she didn’t really want to talk too much more about the issues.)

-

My other central question: Does the camera know you’re a girl? “I was [chosen] and I get chosen to work on certain films because of my gender[,] my ability to work with certain subjects on a different level. Whether I frame people differently, whether I visualize people a different way, I couldn’t tell you.” With documentaries, “it’s so much about engagement with the subject,” especially when topics are sensitive. I immediately thought of Sofia Coppola trying out lingerie for Scarlett Johansson, who said:

In the first scene in the movie, I am photographed from the back in sheer pink underwear. Now, I’m not a really physically fit type of person, and I was afraid to wear the underwear. Sofia said “I’m going to try on the underwear and show you what it looks like. Then, if you don’t want to do it, you don’t have to.” Well, I’ve been directed by Robert Redford, who is very handsome, but I can’t imagine him suggesting that. Only a female director could get me to wear the underwear. And we shot it.

My old friend shot some safe-sex videos with some rent boys a long time ago and they demanded he be wearing no more than his underwear, which he did. And of course on the fabled Weekend they could shoot the scenes of actual sexuality basically only because the directrix of photography was a woman. Now, I find that interesting given that the director is gay, and maybe what they’re saying is a straight guy would have queered the whole scene.

-

Do your male and female students approach the hardware differently? Girls have “been conditioned to not really be that interested in the hardware.” (Dirse grew up on a farm, she says, and has been around engines all her life.) “I will find the young women will stand back. One or two may come forward. But 90% of the young men will come forward and immediately want to touch the hardware. And I just think that’s social conditioning, to be quite honest. My role as an educator is to get rid of that” because they’re there to learn the equipment. I imagined Ripley demanding “Show me everything” on the weaponry in Aliens. (And she needed it!)

She sees no difference with gay-male or lesbian students. (I asked.)

-

Should 50% of cinematography jobs go to women? “If they have the skill set. They first need to get to that point. They need to sort of shed their inhibitions, [to] embrace that world and do it. But they also need the support. I thought by the time that I reached where I am now at an age there would be 50% women cinematographers, having been one of the first, but you can’t change society. Yet it’s very difficult. Should we have 50% aboriginal people doing the work other people do? These are very difficult questions to answer. The key thing is to start at the educational level.”

Christine Bujis

Christine Bujis wrote in to note a few things, among them her background with hardware and fascination with cameras – broadly comparable to Dirse’s. She also related a tale of getting “zero support from my union” when she tried to move up in the ranks. (I can’t figure out a way to fact-check her story, which is a bit of a pity, and even if I did start making calls I expect I wouldn’t get an answer.)

At any rate:

Women definitely tend to have an innately great eye for composition versus men. (And for more evidence of this, just look to how many visual-based industries are female-dominated – home design, makeup, clothing design, etc.)

And basically all the men there are gay.

A female photographer can often pick up a camera and “get” composition much faster than a man. I think women in general naturally have a better sense of composition, colour, and lighting than men. I think women also bring more a more “romantic” æsthetic, if that makes sense. We are less interested in the slick, sexy sports-car ad lighting, and more interested in the dreamy summer’s-day lighting…. This is also just my personal opinion.

I also teach, and find it interesting that in my beginner classes I tend to get more women. In my advanced classes I tend to get more men. I think women are more modest when it comes to learning style – they always assume there is more they need to know, that they’re not yet an expert. Men tend to be confident (and in many cases, overconfident) and assume they already know a lot of things and can skip the beginner stages. So women will tend to underestimate their skills, and men seem more likely to assume they can do it, even if they can’t.

This is consistent with first-year computer science and is one reason why Harvey Mudd College puts expert first-year students (mostly guys) in their own classes so true beginners won’t feel stupid.

(I did get one other response, but we haven’t talked on the phone yet. I’ll update this post if I find out more.)

Maya Banković

(2013.07.25) Later, Maya Banković got in touch to say (excerpted):

In all honesty, I cringe a bit internally any time a director or producer tells me that they’re after a “female perspective.” Sure, I might, and probably do, have one seeing as I identify as female, but this is just one facet of my identity and therefore just one force shaping my perspective overall. By that token, they could (and should) also be citing my age, my personal experiences including my relationship to the subject matter, the places I’ve seen in the world, the films I’ve watched and gleaned influences from, the type of art and music I’m into, the type of family I come from, my socioeconomic class, the fact that I grew up in the suburbs, the fact that I’m second-generation Canadian, and on and on when it comes to elements that might influence my unique contribution to the visual language of a film I shoot.

That gender and gender alone continually serves as the essential cornerstone in what female cinematographers might bring to the table creatively boggles my mind to no end. […]

I do use the word “collaborator” and use it pretty much exclusively when discussing the people I work with. I expect for things to get personal between myself and a director. Maybe I’m after a different type of working relationship or experience than other cinematographers out there, [preferring] this type of experience rather than the heirarchical employer-employee relationship often found in the film industry (and yes, this probably includes the structure of TV-series work). […]

I put a ton of emphasis on teaming up complementary personalities in my lighting, grip, and camera departments. This is much more important to me than sprinkling the right amount of hormones throughout the crew…. Nevertheless, I generally prefer to not highlight those things as personal selling points or hard proof of any real advantage or disadvantage one might have being female on a film set. Personality and your body of work will always take precedence.

“Too few”

It is not straightforward or obvious that there should be “more” women in cinematography, or a certain number, or that half of cinematographers should be women. It also isn’t clear that having one year in which no woman directed photography on a Canadian TV show represents anything. If you disagree and wish to debate the point, now you actually can! Because – unlike Ryerson and Women in View, and for that matter unlike the Canadian Society of Cinematographers – I actually committed journalism and did some research.

A job nobody wants to be 50% female

Here’s five roofers who – going by appearances – drove down from Barrie on a 30° morning in a truck without air conditioning.

To paraphrase Susan Pinker as I so often do and in fact already have done here, women decided certain male jobs were the best ones and simply demand half the slots. But nobody demands that half of all roofers be female.