I’m not sure I backed a winner with Fabrice Neaud. (It’s “No” [one syllable] not Néaud [two]. And even a perfectionist like me has trouble typing his deceptive surname properly.)

Since the summer, I have variously sat there with a PDF Webcomic on one monitor and Google Translate on the other monitor (sometimes Bing – each has its strengths), or lying down with either of those services on one’s iPhone. (Once or twice, I was in fact that guy on the subway reading a graphic novel in French.) I put in this much effort to read the original because I discovered Fabrice Neaud in translation. There were two points of introduction.

-

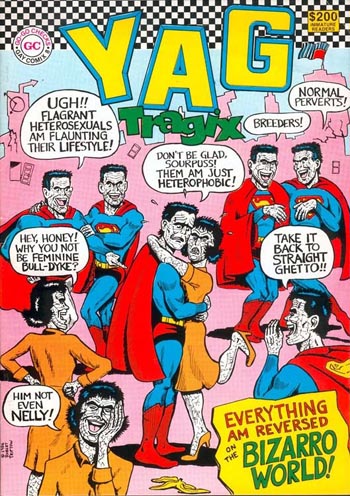

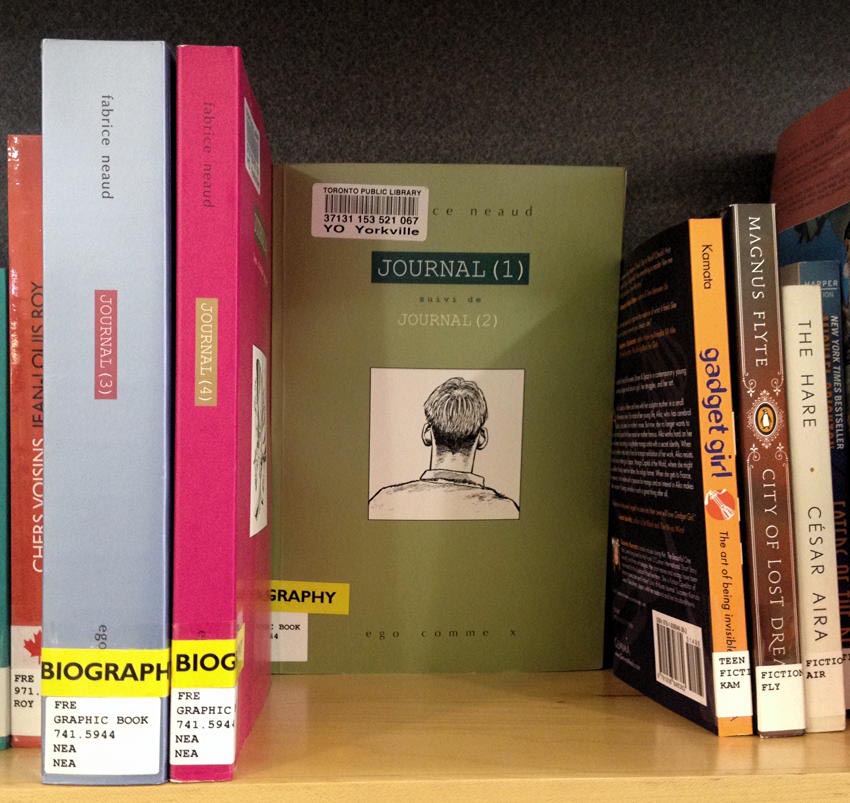

Months ago I lined up with wall-to-wall nerds to enter the marketplace of the Toronto Comic Arts Festival at TRL. There indeed stood tall Justin Hall, editor of the compilation I had heard so much about, No Straight Lines. (I quizzed him on the origin of the Gay Comix [Yag Tragyx] cover I barely remembered: “Him not even nelly!” Of course Justin could rhyme off every fact and figure.) I chatted him up about how I had put in a blue suggestion form for his book, which was taking forever to show up. I’ve got the last hardcover copies here, he said. But days later, my TPL hardcover copy was in hand.

Months ago I lined up with wall-to-wall nerds to enter the marketplace of the Toronto Comic Arts Festival at TRL. There indeed stood tall Justin Hall, editor of the compilation I had heard so much about, No Straight Lines. (I quizzed him on the origin of the Gay Comix [Yag Tragyx] cover I barely remembered: “Him not even nelly!” Of course Justin could rhyme off every fact and figure.) I chatted him up about how I had put in a blue suggestion form for his book, which was taking forever to show up. I’ve got the last hardcover copies here, he said. But days later, my TPL hardcover copy was in hand.

-

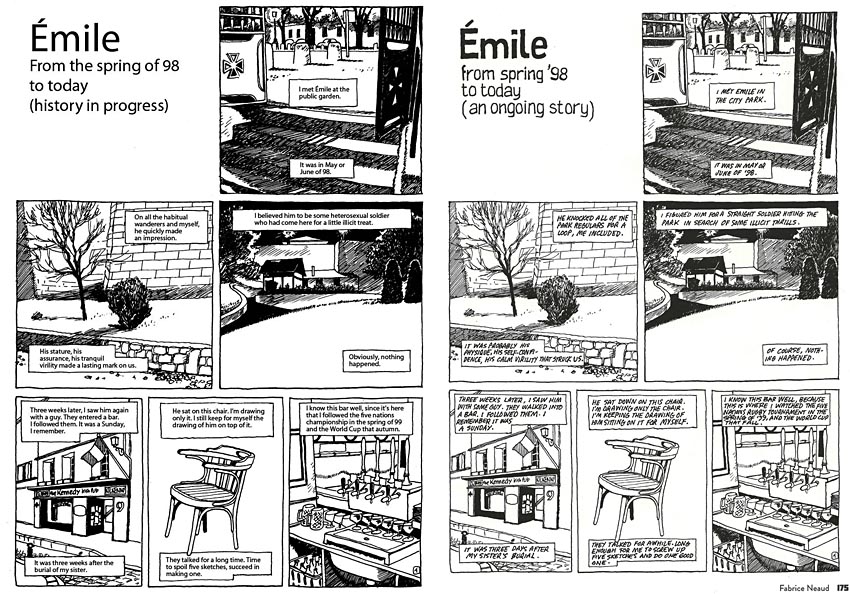

On a slow Sunday morning at my haunt, I turned a page in No Straight Lines and found a strange gripping nearly-dialogue-free autobiographical piece entitled “Émile.” It feels a lot like La Jetée, a recherché reference I am allowed to make given the context and the accented letters. (It turns out there’s an English translation of “Émile” available online, but it’s terrible. Read the version in No Straight Lines.)

Representational art

It’s easy to be impressed by highly representational and lifelike drawing skills, but I know that lifelike illustration is hard to do.

In “Émile,” every hair on every nape of neck is right there in photographic detail. But Neaud writes in as much detail as he draws. After I started reading Neaud in the original I had a hard time believing the vocabulary. The last time I read French this recherché (again) was from Adrian Frutiger.

“Émile” is ostensibly about an infatuation with a soldier. Soldiers, for Neaud, are an archetype. He happens to live near a military training garrison. He sees these guys around, and sometimes they see him.

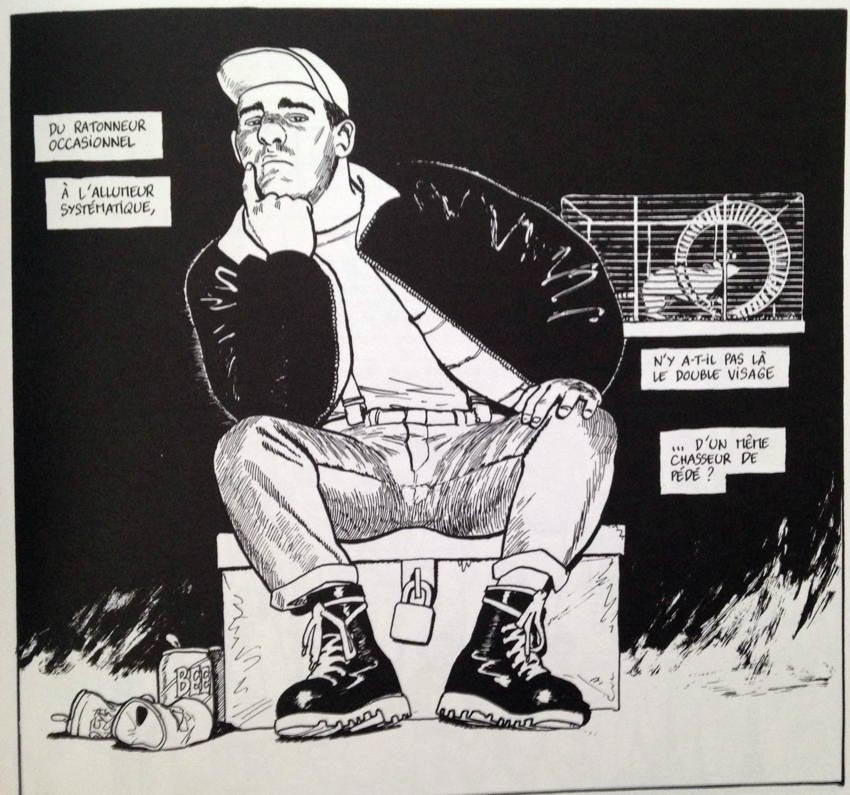

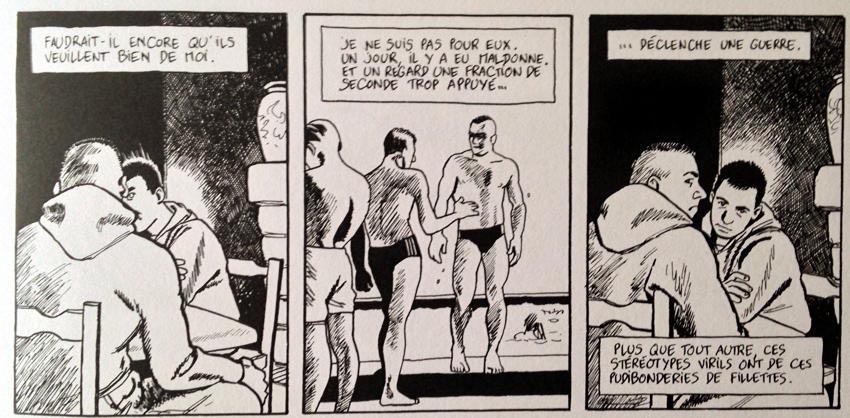

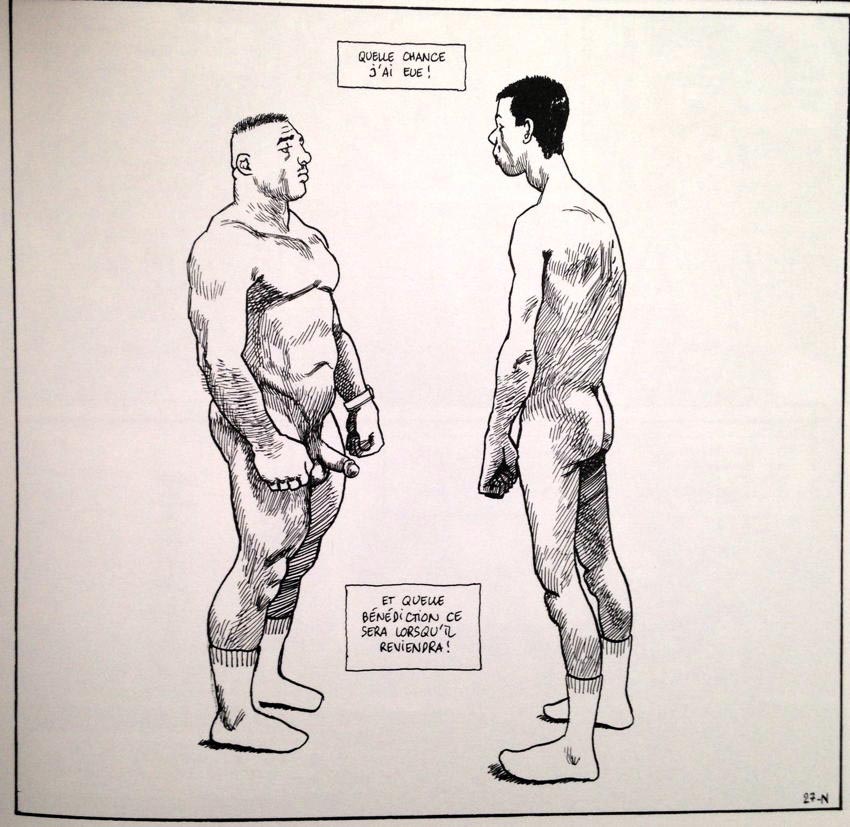

Fabrice Neaud is an archetypal skinny intellectual who lives for, who just cannot get his head around, big strong masculine guys. He especially can’t believe it when, once in a blue moon, they go to bed with him.

But mostly it’s a life of observation from afar – of his beloved ruggers, of soldiers at the training base coïncidentally located in his town, of brutish guys with shaved heads and thick necks. (A lot of his references are to rather trite Hollywood stars – Bruce Willis, Mel Gibson. He should be thinking more of Tom Hardy as Bronson plus Kane, but French and in trackpants.)

Neaud translates into pencil and ink the male hindbrain, which shuts down intelligent thought when confronted with a perfect specimen. Hot girls know this syndrome well; the smart ones use it. The next time you see an otherwise perfectly reasonable guy blubbering away or just staring open-mouthed at a chick with a good rack, imaging what it’s like being gay and coming face to face with a naked rugger or a Marine whose chest is twice as thick as you are. Neaud puts this drool reflex into pictures. (In the immortal scene from Duckman: “Your buckets, gentlemen.” “Buckets?”)

“Émile” is companion to Neaud’s autobiographical project entitled simply Journal. It’s about 800 pages so far in three or more volumes (depending on version; there are four instalments). I can think of a couple of purely literary counterparts (e.g., Knausgård), but if you want every detail of a life told in pictures and cutlines, and in French, there is only one example. He actually gets a lot of press, even in English, just on that point. Nobody had tried this before, apparently. (The whole story ends in 1998. There won’t be a fifth instalment because people in Neaud’s life have issued legal threats over his project. It’s that detailed, and he uses real names and faces.)

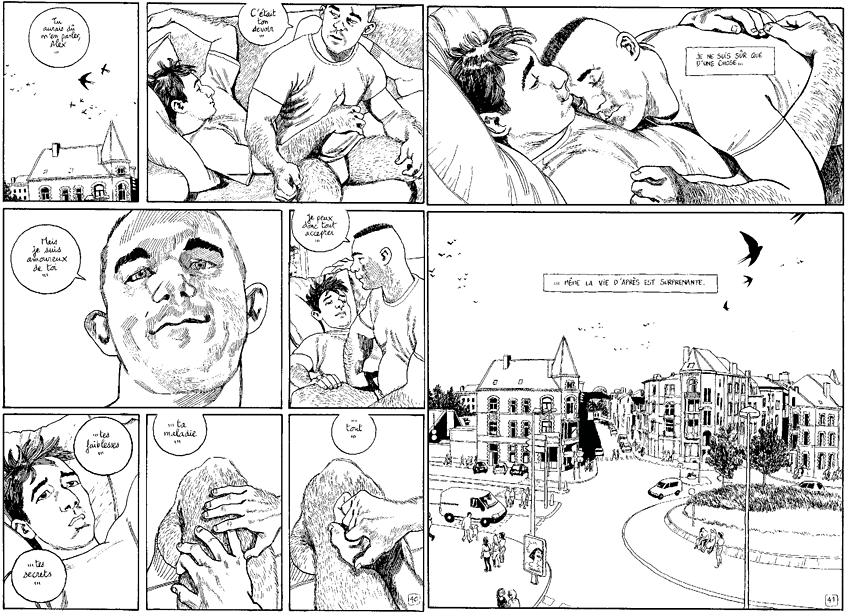

Neaud has the romantic sensibility that gets in the way of enjoying special but irreducible moments. We all have those. My best example is talking to a dashing heterosexualist Brit on the overnight 506 streetcar 20 years ago. A one-night stand is not quite in the same continuum because there has to be a feeling of exceptionalism. Big guys giving a shit about him are rarities in Neaud’s life. They are beautiful unique moments. Neaud’s failing is one we often share. We want beautiful unique moments to last. If they did, they wouldn’t be what they are.

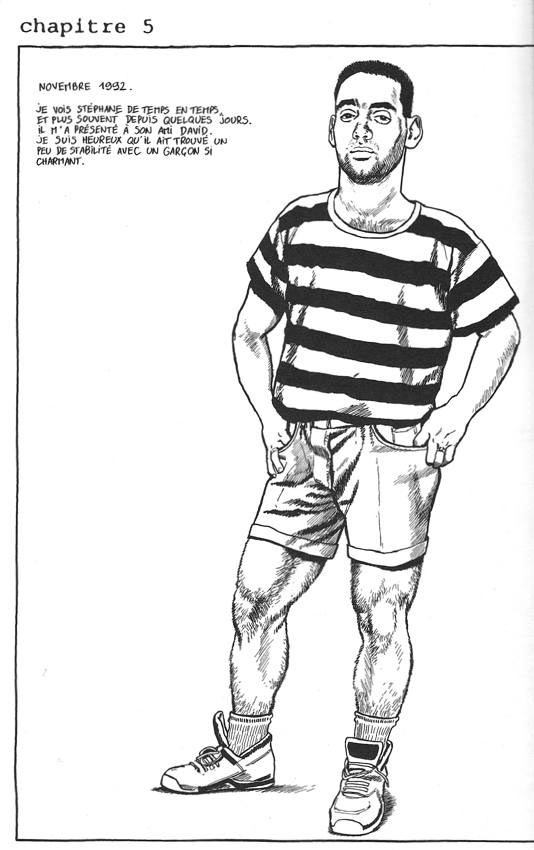

I’m baffled at his devotion to his limerent object de l’époque, Dominique, an ugly bruiser – truly ugly, despite the requisite bodyguard physique. Dominique quotes Nietzsche, is straight or maybe isn’t, and fundamentally hates people, Fabrice more than most. His previous limerent object, a soldier/cook named Stéphane, made so much more sense.

It would be a monumental task to translate this business into English, though Volume 1 did get a Spanish translation. Then there’s the question of who would read it. (I am not totally clear why I did, and feeling like a chump about that kept me from finishing this posting for months.) I submitted a blue submission form to the library (after the longest research phase ever). They ordered one copy each.

I kept feeling bad about this until I realized those copies weren’t moving and I had also given up. I think I oversold this thing to myself and to the library (to no harm in the latter case). I gave up because the entire fourth book, and half the third, were not concerned with the examination of archetypes that “Émile” and the first book had sold me on. In later volumes, Journal became an autobiographical graphic novel – one that took years to put into pictures and words events that are of interest only to Neaud and his artists’ colony in small-town France. I dislike the ugly, antisocial Dominique too much to wade through hundreds of pages about him in a second language.

I kept thinking back to the review of a Voyager CD-ROM, From Alice to Ocean, that I wrote for the Voice 20 years ago. At the time I complained that the story itself was about 20 years old. Autobiography shouldn’t take this long to write and publish for something so inconsequential. Neaud’s problem, then, is half the opposite of Ved Mehta’s – too prolific an autobiographical output for a life of too little interest. There, I said it.

He’s better in short bursts

“Émile” isn’t his only short piece. I found his AIDS-education comic for the Belgians, Alex et la vie d’après, non-trite and effective at is purpose – giving newly-diagnosed positoids something by which to understand their own experiences. (You have to hunt around for a PDF. Or ask me for one.)

There has to be a happy ending, and here Alex, a normal guy with a big nose, wins over a young fella in trackpants who could bench-press Alex with one arm.

Some cartoonists draw endless girls with good racks. Then there’s Fabrice Neaud. The same body type appears in what I consider his straight-up selling out, the science-fiction comic Galactus. It’s the very same guy, only bigger. Switching from autobiography to “superheroes” is like doing bareback porn.

And all the while I read Neaud, I kept thinking that whatever I wrote about him he wouldn’t understand, because, ironically enough, his English is nil. His is a tale told in pictures; mine is not.

Evocative and meaningful homosexualist art projects

I’m being pretty hard on him here, but when he’s dealing with archetypes Fabrice Neaud easily becomes one of the most evocative and meaningful homosexualist art projects I have seen in recent memory. There are two others: iPupo and the hotel portraits of Mr. RENALDI (q.v.), which now are either not online anymore or are hidden away in a weird JavaScript UI that he will not fix after many entreaties to do so.

In weak moments I look at all those things with dreamy wonderment.