Another in a series of postings on CBC captioning (also see the separate page on the topic)

You’d be surprised how difficult it is to explain why subtitled movies must also be captioned.

-

The Brits and Irish cannot even express the concept, as subtitling is called subtitling but captioning is, too. They’re wrong, of course, and have been all along. This isn’t a cute little dialect difference (boot/trunk, elevator/lift) that a descriptive linguist could champion as a fascinating form of language diversity. They’re using the same word for two different things, making them impossible to distinguish. (“I’ve never liked watching subtitles.” Quick: What does that mean?)

This failure to distinguish two separate things leads to inanities like the Irish broadcast regulator’s claiming that subtitling levels on TV should be increased while limited amounts of captioning could be permitted. Every single bit of it is captioning and it’s what they’ve been watching all along.

-

French has only one word for captioning and subtitling, sous-titrage. You can use sous-titrage codé for closed captioning, but doing so limits you to a discussion only of that, not of captioning in general.

-

Then of course there’s the bullshit on Wikipedia, but I shall leave that for another day.

How does this apply to CBC?

Well, the captioning department is run by a Francophone. She speaks English with a rather modest accent and certainly has good fluency. Nevertheless, the sous-titrage/sous-titrage distinction is in there somewhere, and I believe that first-language interference is partly to blame for CBC’s refusal to caption subtitled programming. «L’émission, c’est déjà sous-titrée. On ne peut pas ajouter davantage de sous-titres !»

There seems to be an official belief, grounded in nothing but rampant ignorance, that subtitles are captions. Yes, perhaps they are – at a taverne on rue Ontario est or in the National Assembly or at the Centre Pompidou, but not here.

Why are subtitles not captions? I’ve explained this over and over again, and I challenge anyone to disprove even a single item on this list of differences:

- Captions are intended for deaf and hard-of-hearing audiences. The assumed audience for subtitling is hearing people who do not understand the language of dialogue.

- Captions move to denote who is speaking; subtitles are almost always set at bottom centre.

- Captions can explicitly state the speaker’s name:

- [MARTIN]

- >> Announcer:

- ORIGINAL CAST OF "ANNIE":

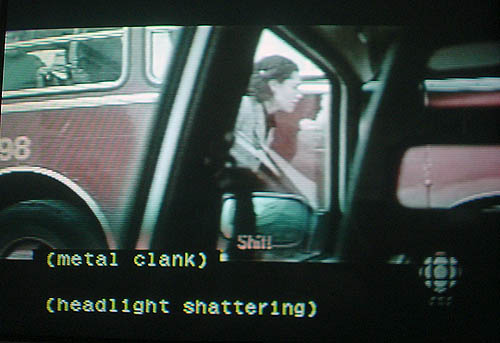

- Captions notate sound effects and other dramatically significant audio. Subtitles assume you can hear the phone ringing, the footsteps outside the door, or a thunderclap.

- Subtitles are usually open (permanent, always visible). Captions are usually closed (selectable; you can turn them on or off). Closed subtitles, however, are now more numerous due to the popularity of DVDs.

- Captions are usually in the same language as the audio. Subtitles are usually a translation.

- Subtitles also translate onscreen type in another language, e.g., a sign tacked to a door, a computer monitor display, a newspaper headline, or opening credits.

- Subtitles never mention the source language. A film with dialogue in multiple languages will feature continuous subtitles that never indicate that the source language has changed. (Or only dialogue in one language will be subtitled.)

- Captions tend to actually transcribe and render utterances in a foreign language, or transliterate that dialogue if a different writing system is used, or state the name of the language being spoken.

- Captioning aims to render all utterances. Subtitles are selective and do not bother to duplicate some verbal forms, e.g., proper names uttered in isolation (“Jacques!”), words repeated (“Help! Help! Help!”), song lyrics, phrases or utterances in the target language, or phrases the worldly hearing audience is expected to know (“Danke schön”).

- Captions render tone and manner of voice where necessary:

- ( whispering )

- [BRITISH ACCENT]

- [ Vincent, Narrating ]

- (Sings like Elvis)

- A subtitled program can be captioned (subtitles first, captions later). Captioned programs aren’t subtitled after captioning.

If you’re a deaf viewer watching a subtitled movie without captions, well, you end up asking yourself a lot of questions:

- Why did that man get up from the couch and open the front door?

- What prompted that teenager to pull a cellphone out of her purse and press it to her ear?

- Whyever did that driver pull over to the curb?

- Why is that starlet wearing a headset microphone and dancing onstage?

- What was the answer to that question?

Subtitlers, whose rampant snobbery I shall also leave for another day, view their job as one of explicitly limiting and minimizing the information represented in subtitles. Hence, as a matter of ideology, they leave out non-speech information (knock on door, ringing phone, siren); they often refuse to subtitle songs or music; and, when translating well-known source languages, they refuse to subtitle common words that, they errantly and arrogantly assume, everyone can hear and understand. As a consequence, a deaf viewer watching a movie in, say, French may never find out whodunit, since the prosecuting attorney’s plain questioning (“Did you kill your wife?”) will elicit an answer that is never written down.

Unless, of course, you caption the subtitled program.

Here is CBC’s official bullshit excuse for refusing to do that:

Sub-titled [sic] programming is not further captioned in normal circumstances. While some individuals may prefer more text to cover the video images, it is CBC’s view that, on balance, the marginal gain from the addition of captioning for the hearing impaired is outweighed by the additional video lost.

Apparently these people think that all the original dialogue will be transcribed and presented in captions. How stupid is that? This implied claim is disproven even by the very few subtitled movies CBC shows with captions, which attempt to caption some non-speech information (NSI) but almost never render any utterances (not even oui or non).

But since this is CBC captioning we’re talking about – a subset of Canadian captioning, which, for prerecorded shows, is already bad enough – the Corpse does not limit itself to one error at a time. CBC is the kind of place that never screws up just one way when it can do a twofer instead. So they’ll do crazy shit like add captions to a subtitled show (NSI only), but use scrollup captioning that just sits there for a couple of minutes after the audio is heard (Lovers of the Arctic Circle, 2006.08.24):

Because obviously it is too difficult to issue a clearing pulse and delete the captions from the screen.

And even though it is quite easy to caption a subtitled show – all you have to do is sit there and play it, filling in the blanks here and there – they still cannot be bothered to individually time and place the 15 or 20 or 60 captions required in such a case. (A two-hour movie in one language has 1,200 to 1,800 captions.) Like Coronation Street, subtitled shows are the kind of programming that isn’t good enough for pop-on captions.

There are, in fact, a few tricky issues in captioning a subtitled show, but the way things are going now, CBC will never even hear what those issues are. (Maybe the Francophone head of captioning should stop me and chat instead of just nodding at me the next time she plainly recognizes me as I walk through the captioning department.)

Uncaptioned subtitled shows prove noncompliance

The Vlug decision required CBC Television and Newsworld to caption everything, not many or most things. Every second of the broadcast day must be captioned. CBC staff and managers are not empowered to exempt entire genres of programming from captioning because they’re too French, too stubborn, too inept, or too ignorant to do what they are legally required to do. CBC is not permitted to decide, “on balance,” that added captions are too much to read. Irrespective of the reason, absent captioning on subtitled programming is, all by itself, proof that CBC is in noncompliance with its requirements.

Now, the question is: Why am I the only one who cares?