When hearing people first watch captioning, they lose their shit when so much as a word is dropped. I don’t know where people got the idea that every single word has to be captioned. And, as this posting will explain, there is no useful way to assign a number to captioning errors.

What we’re gonna talk about

- What captioning actually is

- How captioning errors are measured

- Dropping words from captions, and whatever difference that might or might not make

- An actual example

- And a conclusion

What captioning actually is

Captioning is not transcription; it merely starts with transcription. There are many circumstances where we strive for, and very often attain, verbatim captioning, and other cases where we do not and do not.

But if we use, as a basis, a verbatim transcript (even an idealized verbatim transcript that does not exist in any form), how do we count or quantify captioning errors?

I was thinking about this while reading the many FCC interventions. Let’s start with real-time captioning, that is, captioning produced by a stenographic process. (See photos of stenotype keyboards.) It is ordinarily reserved for live events, but now also used by cheap-ass producers who don’t give a shit about captioning and shop only on price.

Qualified stenotypists can produce 180 words a minute for long periods. That’s actually a conservative estimate. My esteemed colleague Gary D. Robson, who really should start answering my E-mails, writes in The Closed Captioning Handbook: “Real-time stenocaptioners must regularly work at sustained speeds of over 225 words per minute with accuracy of 99% or better.”

That gives us many variables to start with.

- What about unqualified stenographers? There is such a demand for real-time captioning that pretty much anybody who manages to graduate from a training program, even minimally, can work in captioning. But minimally-qualified stenographers may have trouble keeping up with 180 wpm, let alone 225.

- What does “over” 225 words per minute mean? 226? 300? Does this set up an expectation that extremely fast speech can be reasonably captioned for “sustained” periods?

- Now the fun part: If accuracy cannot fall below 99%, doesn’t that mean one word in a hundred can legitimately be wrong or missing? If so, which word?

A bit of linguistics at this point: Content words are those that have meaning in and of themselves in an utterance. Function words connect content words (like of or without in English) or serve grammatical or phonological purposes (like を in Japanese or ли in Russian). (Other details of the difference between the two terms have no bearing on a discussion of captioning.) If you’re captioning 99% but not 100% of a program, are you dropping one content word in a hundred or one function word?

It isn’t true that the former is always worse than the latter. “Not” is a function word; the difference between “guilty” and “not guilty” is substantial. So is the difference between easily-misstroked words like from and for (“left from the airport” vs. “left for the airport”). So which of those two errors is worse? In a courtroom trial, the first one. On TV… well, which one really is worse on TV?

Note also that many untrained commentators fail to differentiate among:

- Real-time captioning

- Live-display captioning (that is, previously-prepared captions that are merely scrolled up)

- A mixture of real-time and live-display captioning (as in the third broadcast of a day’s newscast, where nine out of ten news items are unchanged from previous telecasts but one of them has to be stenotyped from scratch; includes the Australian case of pop-on captions for the pre-scripted portions and scrollup for stenotyped portions)

- Recovered real-time captions that are fake-live-displayed (that is, an error-strewn real-timed text file is merely replayed during a rerun of the show)

- Offline or prerecorded pop-on captions

- Intentionally edited pop-on captions

How do you measure this sort of thing?

The FCC filings give several options.

-

NCI:

[T]he specified accuracy rate (or permissible error rate) should be measured on the basis of number of errors per words written combined with proportion of content written….

- [If one] firm captioned only one sentence of five words during the entire program, but did it without error, using only errors over words written, the accuracy rate is 100%.

- [If a] second firm calculated their captioning accuracy using a combined error rate for words written and proportion of content written – this firm’s accuracy rate was a 99% accuracy rate for words written… and [if they] wrote 99% of all words spoken; the two combined for an error and omission rate of 2%.

The math there is screwy. Captioning 99% of 99% of uttered dialogue means you captioned 0.99 × 0.99 or 98.01% of the dialogue, leaving out 2.01%, not 2%. It’s multiplicative, not additive. One-hundredth of a percentage point can manifest itself as several individual words.

-

AMIC (initial and reply comments combined):

Note that in the case of live programming, misspellings of proper nouns that were not widely and generally familiar prior to the live event or broadcast should not be counted as errors, in recognition of the frequency of news bulletins that identify previously obscure names of places or people (e.g. Lockerbie, Scotland prior to 1988, or Elián González prior to 1999). […]

[W]e believe the appropriate average error rate for live captioning is 5.0%. In both cases, the evaluation of what is “absent” and in error should take into account… mitigating factors. […]

AMIC has not found [NBC’s stated] poor level of accuracy [84%] to be the practice of any of our member companies….

Any issue of captioning accuracy must address two questions:

- Are all the spoken words of the program audio reflected in the written words?

- Are the written words accurate?

The second question cannot be answered without satisfying the first. Some programs may claim an accuracy of 98%, meaning 98% of the words that appear in the captions are correct, regardless of whether or not 100% of the words in the program audio are captioned. The proposed AMIC standard ensures that both components be considered (along with a third critical component – timeliness). A claim of 98% accuracy is correct according to the AMIC formula if the captions truly reflect 100% of the program audio. If, however, the captions only reflect 90% of the program audio, the accuracy score would drop to 88%.

Note here that they are at least using the correct math (0.98 × 0.9 = 0.88).

Consider what it means for captioning to display no more than five out of every six words accurately, as an 84% standard would yield. Mistakes can, of course, take several forms. They may consist of missing words or phrases, incorrect words, or misspelled words. Take the first sentence of this paragraph.

-

At 84% accuracy, it might read: “Consider what it means for to display no more than out of every six words, as an 84 standard would yield” (missing words).

-

Or it could read: “Consider what it means no more than five out of every six words accurately, as an 84% standard would yield” (missing phrase).

-

Or yet again it could read: “Councilor what it means for captioning to display no Morgan five out of every words accurately, as an 48% standard would yield” (misspelling; missing and wrong words).

We can’t conceive that any of the above versions of the sentence would be acceptable to a caption viewer. Every one of these examples would be measured, by AMIC’s suggested specification, at exactly 84% accuracy, and none of them make any sense. If AMIC’s recommendation of 95% minimum accuracy is adopted, there would be, on average, no more than one error in this 25-word sentence.

Interestingly, AMIC completely dodges the issue of which word will be in error. The word “not” in “not guilty”?

-

Caption Colorado:

- Transposed words. Each occurrence of 2 or more transposed words counts as 1 error. Words or clauses within a sentence that are out of order as a result of the captioner intentionally moving them, without affecting the meaning of the sentence, are not considered transposed words or errors.

- Adjustments to word count for punctuation and speaker-/story-ID errors. In determining the number of words in a transcript from which accuracy and error rates will be calculated, periods and question marks and speaker and story IDs appearing in the transcript should not be counted initially. However, one word should be added to the total word count for each error counted for these types of errors.

- Adjustments to word count for captioner correction of mistakes. Errors properly corrected by the captioner during the realtime transcription shall not count as errors and the words or errors that were corrected shall not be counted in the number of words in the transcript.

-

WGBH:

Accuracy rates should be 99% or above, calculated

as follows: The total number of all words in a program minus the total number of all errors in that program divided by the total number of all words in that program.

What’s wrong with dropping words?

It seems to be assumed that dropping a word in captioning is always an “error.” In fact, we drop words from captions all the time.

- Some captioners (e.g., the British) have an ideology that captions must never exceed 150 wpm. Although that ideology was debunked by British research, it results in edited captions.

- Some captioners who are lapsed or disgruntled subtitlers (a seriously lapsed and disgruntled lot to begin with) have an ideology that captions may never exceed two lines. (And of course one of those lines has to be shorter than the other. Exactly which one is the subject of duelling ideologies.) This too leads to editing.

- On rare occasion, we can drop a word to fit two sentences into two discrete lines, with a carriage return between them. If the word is superfluous (as some are: “very, very hungry” vs. “very hungry”), this can increase readability compared to ending a sentence in an orphan.

- In encoded captioning, we simply may not have enough time to transmit all necessary words even if we do things like set the caption flush left and remove other control characters. In cases like that you have to edit.

- If a group of people all mutter different utterances with a similar meaning, we may be able to render most people’s utterances but not everybody’s (or we’ll caption as [all murmuring agreement]). Other cases of simultaneous speech are similar.

- If onscreen graphics are extensive and stay there for a long time, we may have to edit so that captions can be displayed in meaningful single-line chunks.

- We may specifically edit for reading level. The only credible example of this in living memory is the version of Arthur on PBS with two caption tracks. The promised research documenting the study of these verbatim vs. edited captions has not been published, and I doubt it ever will be.

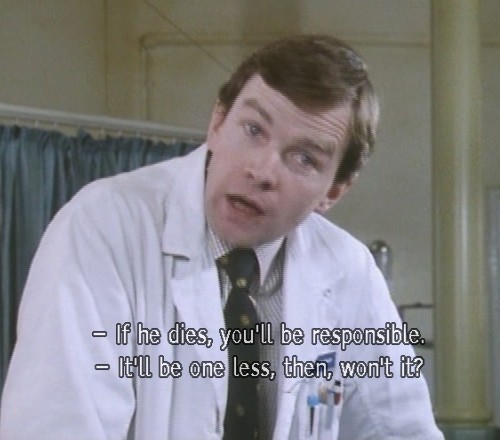

When you combine British and subtitling ideologies, you end up lying to the viewer, as in this example from The Singing Detective, where the doctor actually says “If he has another heart attack, you’ll be responsible”:

“Has another heart attack” and “dies” are not remotely equivalent. (Note also the use of the discredited Tiresias font.)

Too-fast captions

If you’re concerned that people can’t keep up with verbatim captioning, eyetracking and other research (chiefly by Jensema) shows that it isn’t a problem up to about 180 wpm, with ≥200 wpm captioning tolerable for some periods. Besides, deaf activists can’t be demanding verbatim captioning of news and live events on one hand and edited captions on prerecorded TV on the other. And of course some people cannot keep up with verbatim captions; the solution to that problem is a second set of captions (plausibly attempted, as we’ve seen, only once), not a sacrificing of the source text that every viewer must read.

Note that dropping entire sentences is a special case of dropping words. There are plausible reasons to do exactly that. In some cases an entire reaction shot will go uncaptioned, a discrepancy you can detect visibly and audibly. Yet it is sometimes necessary. (The best example I know is one I do not have on tape: Compare the CBC and PBS telecasts of A Very British Coup circa 1989.)

While verbatim captioning is desirable and possible a lot of the time, sometimes it is neither of those things. So let’s dispense with the idea that something’s automatically wrong with captioning if it is edited. Sometimes editing is inevitable or desirable.

So how do you count captioning errors?

Let’s take an example

By amazing coïncidence, while writing this, The Daily Show – a program with consistently lousy and unremediated real-time captioning (by WGBH) – featured a segment that suits the discussion perfectly (on 2006.03.13).

It isn’t my fault that the segment is a bit risqué all the way down to the level of the segment’s main joke. I didn’t pick the segment because it was risqué; it merely happens to illustrate the issues perfectly and also is a bit outré. (But really, what else could we expect from Sharon Stone? I write as someone who has in fact watched the audio-described version of Basic Instinct.)

- I transcribed this segment’s utterances my own way (but with American spelling).

- I left out non-speech information that really should not be left out by anyone (especially the long periods of audience laughter and applause).

- I laboriously transcribed the actual caption text (changed to mixed case).

- I had to guess at an apparent Yiddish passage. I also found Sharon Stone nearly unintelligible at one point. Those two examples are rather unusual for me, since I almost never find anything on television unintelligible (even typical foreign-language passages). Maybe I have an aptitude for this stuff.

| Speaker | Transcript | Caption |

|---|---|---|

| Stewart |

And, uh, it feels weird to celebrate his death. And yet… not. You know it was just probably to get back at Saddam Hussein: “Oh, you in the headlines? Nuh-uh!” Let’s turn to another troubled region – seriously, as I make an emotional segue for the people at home. Not too long ago, hopes for a Middle East peace rested on a heavy-set man named… Sharon. Well, it’s a sign of how desperate things may be now that hopes rest on a woman named Sharon, but pronounced “Sháron.” Specifically, Sharon Stone. The actress – the actress and noted vaginist recently visited Israel in the company of former prime minister Shimon Peres as a special guest of the Peres Center for Peace. Siz avass. Now, um, seriously, what are you doing out there, Shimon Peres – using the Peres Center for dating purposes? Perhaps I can give some insight into calls he must have made before Ms Stone: “Hello. Is this Jessica Alba? This is Shimon Peres. We need you to help jump-start talks with the Palestinians. Bring your costume from Sin City.” But actually, it’s a very serious issue. Basic Instinct 2 actress answered the important questions of the day. |

It feels weird to celebrate his death. Yet not. He died just to get back at Saddam Hussein. Are you in the headlines? No, no. Let’s turn to another troubled region. Seriously as I make an emotional Segway for the people at home. Not too long ag, hopes for a Middle East peace rested on a heavy set man named Shafern. It’s a sign of how desperate things may be now that hopes rest on a woman named Sharon, but pronounced Sharon. Specifically Sharon Stone. The actress and noted vaginist recently visited Israel in the company of former prime minister Shimon Peres as a special guest of the Perez Center for Peace. Seriously what are you doing out there Shimon Peres using the Center for dating purposes? Perhaps I can give some insight into calls he must have made before Ms Stone. “Hello, is this Jez Ka Alba?” This is Shimon Peres. We need you to help jump start talk s with the Palestinians. Bring your costume from Sin City. ” But actually, it’s a very serious issue. Basic Instinct 2 actress answered the important questions of the day. |

| Stone |

People just are sitting there going like, “I don’t care what she’s saying. I don’t care what she’s saying. I just want to know: Is she naked? Does she get naked in that movie? Is she naked? Nude nude nude naked. Do I see her boobies? I don’t care what she’s saying. I don’t care. I don’t care. Is she naked?” So let’s just get through to that: Yes! |

People just are sitting there going like, I don’t care what she’s saying. I don’t care what she’s saying. Does she get naked in that movie? Nude, nude, nude. Do I see her boobies? I don’t care. Is she naked? So let’s just get through to that: Yes! . |

| Stewart |

“Yes, uh, Jon Stewart from Horny Man Times. I have a followup? Um, at what minute mark does that happen? You know, when you’re, uh, flippin’ past the movie on cable and you wanna know – oop!” Actually, Miss Stone recounted Miss Stone’s bravery. |

Jon: This is Jon Stewart from Horny Man Times. I have a follow-up. At what minute mark does that happen? You know, because I’m flipping past that movie on cable I’m going to want to know. Actually, Miss Stone recounted Miss Stone’s bravery. |

| Stone |

I said I was going to Israel. A lot of people went, “You can’t go there! You can’t go to Israel! What are you going to Israel for? You can’t go to Israel – it’s in the middle of a war!” |

I said I was going to Israel. You can’t go to Israel. What are you going to Israel for? They’re at war. |

| Stewart |

It’s always good to have a calm person in a war zone, don’t you think? |

Jon: It’s always good to have a calm person in a war zone. Don’t you think? |

| Stone |

And I called my publicist, who’s this great Jewish woman – |

And I called my publicist, who’s this great Jewish woman. |

| Stewart |

Seriously. Some of my best people-who-arrange-things-in-my-life are Jews. But lest you question Stone’s commmitment to peace in the Middle East, she’d have you know, quote, “I would kiss just about anybody for peace in the Middle East.” Dude, you kissed Steven Segal for scale plus ten. As for what accounts for her passion, we’ll leave her the last word. |

Jon: Seriously, some of my best people who arrange things in my life are Jews. But lest you question Stone’s commmitment to peace in the Middle East, she’d have you know, quote, I would kiss just about anybody for peace in the Middle East. Dude, you kissed Steven Segal for scale plus ten. As to what accounts for her passion we’ll leave her the last word. |

| Stone |

I was asked to come here, and I came in my faith. |

I was asked to come here, and I came in my face. |

| Stewart |

I’m just gonna hope she doesn’t have a lisp. Sure she meant “faith,” not— By the way, I think next week she’s a guest on the program. That should be really, uh… she’s gonna hate my guts. |

I’m just going to hope she doesn’t have a lisp. I’m sure she meant faith. By the way, I think next week she’s a guest on the program. That should be really… she’s going to hate my guts. |

So what just happened there?

That’s 515 words in 4:05, or an averaged 126 wpm, which is nothing. Complicating matters was the speed at which batshit-crazy Sharon Stone spoke. It bordered on ululation. I’m pretty sure this is what a “banshee” sounds like. The burst rate during these ululations is higher than 126 wpm, though I didn’t calculate it.

The captioning deleted several words, misrendered others (ag, Shafern, Jez Ka), and added occasional speaker IDs. It got a few difficult words right, including the neologism vaginist. Punctuation was quite poor. The pun based on pronunciation (Sharón/Sháron) wasn’t even attempted. The captioning has 471 words (including added speaker IDs), for a gross error rate of 44 words or 8.5%. This sample would flunk any numerical standard proposed in FCC filings, though it exceeds NBC’s 84%-accuracy claim by 7.5%. Yet the captioned passage not only is grossly understandable, it has nearly all the detail of the original.

However: I would still flunk the entire passage because the captionist killed the joke. Still want to put a number on that? OK, how?

Caption errors are qualitative

My working hypothesis is that caption errors are qualitative, not quantitative. You may be able to apply numbers to them or even “measure” them, but numbers and measurements have little real-world meaning.

Had the Daily Show gotten 99% of that segment correct, it could still have flubbed five words. What if those five words were Shimon Peres, vaginist, boobies, and Jewish? Serious errors, right? But totally permissible.

What if the captionist rendered every single word correctly except for faith? I don’t see how the real-world results are any different from that scenario, with its 99.8% accuracy. You still kill the joke.

I cannot support any of the FCC intervenors’ suggestions at any level beyond the most general. Of course 95% or 99% real-time captioning is better than 84%… most of the time. A vaunted 5% or 1% error rate can still produce captions that are understandable but futile. At best you are describing a confidence interval: Nine times out of ten, an error rate of 5% or less produces good captioning. But what happens in that tenth case out of ten?

This is not an objective process

Errors in captioning can be diagnosed objectively (you wrote the wrong word; you left out a word), but the significance can be determine only by experts. I see two kinds of expertise here:

- A deaf or hard-of-hearing viewer, who finds the captions confusing or incomprehensible.

- A hearing viewer, who can compare the source audio and captioning.

Both groups need to have an understanding of the captioning process. There are times when a hearing person’s explanation can trump a deaf person’s confusion or incomprehension. (Of course I’m going to say that because I’m a hearing expert. We really can spot mistakes that deaf people can’t because we can hear. I’m sorry if this offends your sensibilities, but if you try to marginalize hearing expertise in captioning you’ll end up with shittier captioning, which you’re already seeing, or no captioning at all. Think about it.)

The best we can hope for is expert agreement, as found in scientific evaluations of unquantifiable phenomena. If, say, three out of five deaf viewers could not understand a show, and three out of five informed hearing people believed the captioning errors could reasonably have been avoided, then you’ve got a problem. What you don’t have is a number to attach to the problem, or at least the kind of number the FCC and intervenors seem intent on locating – because there is no pot of gold at the end of our captioning rainbow. A simple percentage-value error measurement is meaningless and beside the point.